HERE COMES TROUBLE SHOOTING

That portion of the foliage of trees forming the uppermost layer of a plant community is called the overstory. But just as critical to the health of that community is what’s called the understory: everything else in a tree down to its deepest roots.

As with trees, so with universities, in particular the School of Biological Sciences (SBS) at the University of Utah. There’s an overstory of students learning, teachers teaching and faculty doing research and publishing their results and making broad impacts everywhere — an overstory of laboratories and facilities continually being built and remodeled. But the understory of that enterprise is, well, its own story. And it’s made up of a fleet of skilled staff that makes the whole shootin’ match run smoothly.

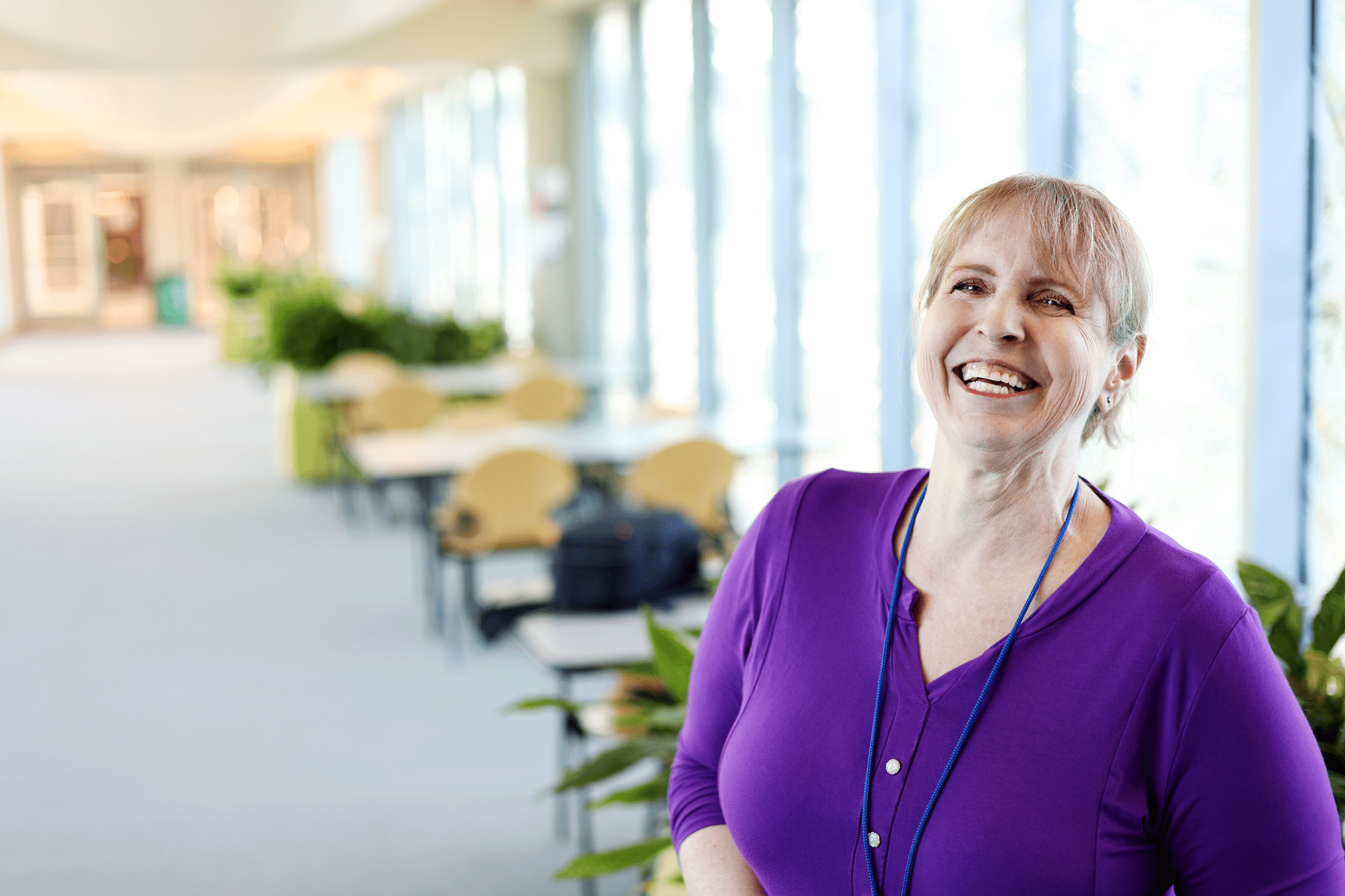

SBS Administrative Coordinator Karen Zundel is the epitome of that understory. Winner of this year’s College of Science Outstanding Staff Award, the twenty-year veteran in what is now the School of Biological Sciences has pretty much seen it all. But to talk to her about her work, her contributions and her stamina is like pulling a sequoia out by the roots (not that anyone would dream of doing that these days).

“Everyone speaks very highly of you,” she is told. “I was excited to meet you.”

Zundel’s response: “Well, we have a really, really terrific faculty. You know, some of the intelligence just sometimes makes my jaw drop.”

It is true that SBS, one of the largest academic units on campus (47 tenure-line faculty with four more waiting in the immediate wings), is well-regarded, with a large footprint of scientific inquiry, from plant biology to mammals (including Right Whales off the coast of Patagonia); from cell and molecular biology to ecology; and from mitochondria to vast forests — data sets plotted for miles and years on both the x and the y axes.

It’s also true that SBS is shot through with a high volume of grant money flooding in while sporting a strong claim to gender-equity, rare in any STEM discipline. The School also claims Utah’s only Nobel Prize winner, Mario Capecchi who did much of the research that led to his acclaim as a faculty member in what was then the Department of Biology.

But what about that understory? What pilings of support exist under all that canopy of excellence? No luck hearing about that here; for Zundel, faculty reigns supreme.

“Well, like I say about all of the faculty, I am always just awestruck by the kind of work they’re doing. It’s one of those things where some people that are not as intelligent as they think they are and are self-important that are kind of a pain to deal with. All of these people [in SBS] are extremely intelligent and genuine and just a joy to work with.”

It’s a generous sentiment by biology’s administrative coordinator and all-around shooter of troubles but one that others might find more nuanced. “The university is a series of individual entrepreneurs held together by a common grievance about parking,” Clark Kerr once said somewhat tongue-in-cheek. The first chancellor of the University of California, Berkeley and twelfth president of the University of California was never affiliated with the U, but he could have easily been talking about the wide swath of life science studies and its faculty at the School of Biological Sciences. And what Kerr never did say was who kept those perpetually unhappy-about-parking faculty happy and productive everywhere else.

Credit: 365 Seattle

Zundel isn’t about to give away the hows, whys and wherefores of what it’s like to be the kingpin of a celebrated understory as large as that of U Biology’s. How does she administer the labs and classrooms of as many as 16 faculty members at a time, faculty who earlier relied on her to manage and submit grant applications and then report on the use of those grants later? How do all of the other assistants whom she manages do the same for the remainder of the faculty pool? Ask her about what it’s like, who she is and how she does it, and she immediately detours to the overstory of amazing work being done by faculty.

“No, no, it’s not me. It’s thanks to our faculty. It was a pleasure to help them with some of those [grant] submissions, because, you know, a lot of it is government paperwork. You know they’re brilliant at the science and they go, ‘Oh, I really have to submit a form’ [and I say,] ‘I’ll do that for you.’ But it’s their science and research at the heart of the grant and we just helped with paperwork and forms. [We] made sure they were complying with all the government requirements, even when the instructions are contradictory.”

Perhaps it’s the nature of the job, like a stage manager in a theater, or a forest ranger taking care of hectares of Douglas Fir: have your influence be immeasurably felt but don’t ever be heard or seen; you aren’t the one to take that bow. And Zundel wouldn’t have it any other way. Fortunately, biology faculty at the U who nominated her for the College award are keen to acknowledge Karen’s work, not to mention why she’s so deserving of it.

“Every unit has one person who works behind the scenes and makes things come out right,” wrote SBS Director Fred Adler and David Goldenberg, professor and associate director of undergraduate programs. Karen Zundel “is that person for the School of Biological Sciences.” She is famous for being the go-to person to troubleshoot problems big and small. Additionally, her institutional memory is invaluable, everything from her recollection of fielding members of the public carrying specimens into the front office to find out what they’ve found to ruminating on the life and times of the late, celebrated plant biologist Robert Vickery, a WWII soldier who was witness to the raising of the American flag on the Japanese Island of Iwo Jima.

But beyond Zundel’s being the in-house historian and trouble-shooter, biology professor Dale Clayton puts a finer, somewhat comical, point on it, referring to Zundel’s acumen managing faculty similar to “herding feral cats.” Tasks include travel arrangements for faculty

Sampling of denizens making up the SBS “Understory”: Jason Socci, April Mills, Karen Zundel and Jeff Taylor.

and the “convoluted process of wrangling visas” for international faculty. She manages biology’s website updates as well as the messaging on TV monitors in the halls of biology. “Despite our interesting collection of personalities,” quips Clayton, she “has the power to embarrass anyone with a few strokes of the keyboard, “ … however, she has yet to humiliate anyone. It would be fascinating to know how often she has been tempted.”

That sort of hubris doesn’t likely live in Zundel. She not only has high regard for faculty, but for staff — even as the stable of administrators has declined recently while faculty membership has grown. She mentions, in particular Ann Polidori, executive assistant to the director and others in the front office and on the front lines of the biology hustle.

“We have got really good staff, and most of them have been with us for a while,” Zundel explains. “On the administrative side, it’s really fun to work in it, [making] the department run. And there’s nobody that goes nuts, [or says] ‘that’s not my job.’ So they’re just a fun group of people to work with.”

Outside of work, the Salt Lake City native loves to travel, especially to the Pacific Northwest and Southern Utah, singling out the viewing the trove of rock art in Nine-Mile Canyon north of Price. She also loves to read, in particular, “cozy mysteries.”

So it turns out the understory is the overstory and vice versa. Which suggests, in true biological form, that the total organism of SBS is like Pando—the stand of aspens spreading over 106 acres in central Utah with an interconnected root system that makes it the largest living organism on earth. And like Pando’s 47,000 genetically identical stems, the organism of School of Biological Sciences is a holistic one, interconnected but as resplendent in its totality as are the individual, reflective and tremulous leaves of a single quaking aspen.

An impressive story — but above and below —if there ever was one, and Karen Zundel is one of the reasons why.

By David Pace