Letters from the Galápagos Islands

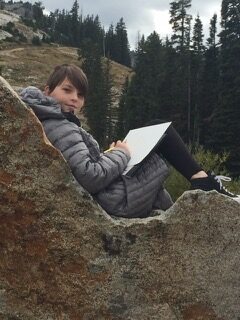

Our South American correspondent Sonora “Nora” Clayton happily embarked on an excursion of a lifetime in February of this year: the Galapagos Islands off the coast of mainland Ecuador. The middle-schooler was embedded in the Clayton/Bush lab (Dale Clayton and Sarah Bush also happen to be her parents.)

It was a first-hand view of research into parasites of birds, and her weekly, illustrated letters each began with the familiar ‘To whom it may concern.’ The project was followed by Utah school teachers and has now been archived.

“This expedition’s purpose is to study avian vampire flies (Philornis downsi),” wrote Nora in the first letter before leaving Salt Lake City, “and how these flies affect finches and mockingbirds in the Galápagos Islands. So, we’ll pack spotting scopes for watching birds, a field microscope for identifying flies, nets, and banding equipment so that we can give each bird a unique colored bracelet for identification. Most of these supplies are [currently] in a pile on our basement floor.”

It wasn’t an easy venture, not only because of the distance, but because of Covid-19. The entire team had to be tested repeatedly before, during and after their stay following international travel protocol.

The team spent most of their ten weeks on the Isla Santa Cruz at the Playa El Garrapatero field site. On Santa Cruz, wildlife was, well, everywhere: Sally Lightfoot crabs, cownose rays, geckos (which show up everywhere), iguanas, seals and the signature tortoises that based on the submitted photos looked like the size of the original Smart car. An excellent (and a little spooky) photo of sharks through filtered light graced letter #5, flanked in other letters by pen-and-ink and water-colored drawings of longhorn beetles, curious-looking botanicals… even two skulls, one of a dolphin and another of a whale!

The letters were far more than the scribblings of a tourist. Nora helped explain the research in detail, including their main subject: Philornis downsi: “Originally, it was suggested that the fly be named ‘Vampire Fly.’ That name was rejected, because evidently it could be mistaken for a fly living on vampires. As surprising as it may be, Philornis lives on a slightly less chiropteran host: birds. So, the name was changed to ‘Avian Vampire Fly.’”

The fly is a parasite on the mockingbird, so the team was kept busy tagging birds and peering into their nests through a “plumber’s camera” perched on the top of a pole.

But it wasn’t all about work for Nora and the rest of the team. “Puerto Ayora isn’t a very big town,” explained Nora about the closest settlement to their research site, “so people walk almost everywhere. …In the evenings our group usually walks to one of the outdoor kiosks for dinner. …On Friday nights, the main street called ‘Avenida Charles Darwin’ is blocked off so that people can walk in the street and go to the shops.”

The University of Utah team also visited giant sinkholes called “Los Gemelos” aka “The Twins.” This was up in the highlands which are greener than the lowlands, with trees called Scalesia that are actually more closely related to a daisy than to other trees.

Back down in the lowlands, Nora reported, “cactus spines in our shoes aren’t ideally tropical, and the dry plants and sharp lava rocks aren’t quite what Darwin expected….” A photo of her pulling those spines out of her shoes gives the reader an up-close-and-personal perspective.

Following their research in the Islands, the Clayton/Bush team set off for a side trip to Amazon region of Ecuador. But per usual, school work—even in faraway South America—didn’t wait. “We finished packing for [the city of] Quito this morning. I took a final exam for science, so I’m almost done with schoolwork until we get home. We’ve been talking with our teachers in Utah this week to have our tests unlocked early so that we can take them before we” leave for the mainland.

On their way to Tiputini, they stopped to look at wildlife and birds, along the way, including colored tanagers, thrushes and oropendolas, as well as hummingbirds fighting for a feeder. “We even heard a Macaw.”

Perhaps it was fitting that the only family photo we received was at the Biodiversity Research Station in front of a giant fig tree which, according to Nora’s father, “may have as much biomass as all the trees at our Galapagos field site combined!” Even so it was a reminder to both the research team and the eager readers of Nora’s “Letters from Galapagos Islands” of just how big and impenetrable our natural world is, even for scientists.

As for Nora Clayton that natural world will continue to pique her curiosity as both a researcher and an artist. Youth is definitely on her side. For now, it’s back to a more traditional classroom in Salt Lake City.

by David Pace

You can read all of Nora’s letters here.

Inspired? Make a donation to help SBS recruit young scientists to our our celebrated programs, ranked #13 in the nation for public universities by U.S. News & World Report.